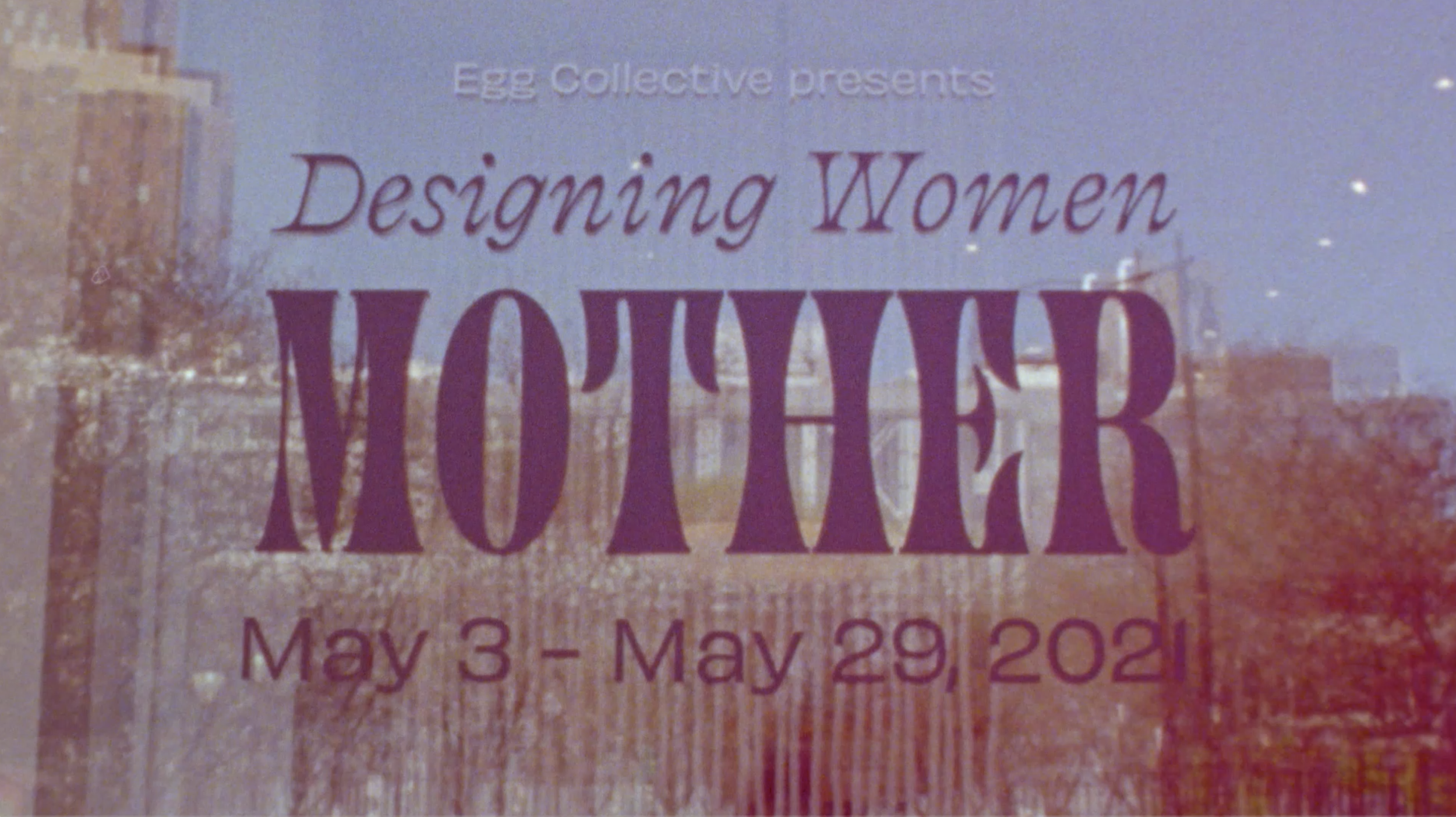

DESIGNING WOMEN III — Mother

We are proud to present Designing Women III: MOTHER, the third installment in our ongoing exhibition series celebrating the many and diverse women whose work has shaped the history of art and design. Featuring work by 28 contemporary and historical artists and designers — each of whom is also a mother— this exhibition invites reflection on motherhood in all its complexity: as a source of life, a role, a burden, a blessing, and a bond.

While the visual scope of the show is well documented alongside our previous Designing Women exhibitions here, this edition of the journal takes a different approach. Instead of relying on images to tell the story, we’ve chosen to foreground the voices behind the work.

What follows are quotes from a selection of participating artists and their children, as well as a letter from artist, mother, and co-curator Tealia Ellis Ritter. Above is a short video featuring the voices of a few of the remarkable creators whose work filled our gallery.

Louise Bourgeois

I have three frames of reference … my mother and father … my own experience … and the frame of reference of my children. The three are stuck together.

Loretta Pettway Bennett

I am an offspring of some of the great quiltmakers from Gee’s Bend. I came to realize that my mother, her mother, my aunts, and all the others from Gee’s Bend had sewn the foundation, and all I had to do now was thread my own needle and piece a quilt together.

Faith Ringgold

No other creative field is as closed to those who are not white and male as is the visual arts. After I decided to be an artist, the first thing that I had to believe was that I, a black woman, could penetrate the art scene, and that, further, I could do so without sacrificing one iota of my blackness or my femaleness or my humanity.

Elizabeth Atterbury

I keep thinking about my mom and her two children, and me and my two young kids now. Two forms held by one. And then to think that my kids were inside my mother’s body too, as eggs, inside my body, inside her womb. Another layer of nesting… Even last night, when I woke up and couldn’t fall back asleep, my mind drifted … to thinking about the arrangement of bodies on the bed. My husband, straight and tight against one edge; my son, crooked along the top of the bed, head under a pillow; my daughter, a small hyphen in the middle of the mattress; and me, my body snaking around my daughter and the cat, tucked behind my knees. I thought of this arrangement not from my tangled, immersed perspective, but from above.

Gae Aulenti

Architecture is a male profession, but I never took notice of that.

Carmen Winant

Just a couple weeks after I gave birth (the first time), I remember reading an interview with the artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, and she was talking about how in 1968 after she gave birth, she was shocked that no one asked about it. She said something like, ‘Weren’t they curious about what it felt like to create life? But with no language, it was like I was mute.’ And I wept when I read those words because I was undergoing a similar experience, having never recognized it for myself. I felt more than eager to talk about the experience; I felt like it was necessary. And for whatever reason—because people wanted to respect my privacy or because they didn’t know how to talk it—it felt like this immensely cloistered experience. I didn’t want it to be, nor do I feel like it should be.

Marie-Laure Bonnaud-Vautrin

My father, Jacques Armand Bonnaud, an artist and interior decorator, worked alongside my mother (Line Vautrin) for many years. Their homes and their workshops were where I grew up, surrounded by craftsmen and artists with whom they worked, so I was totally immersed in the spirit of my parent’s works.

Lucia Derespinis (on designing the iconic Dunkin Donuts logo)

I went into the graphics department, and they had all these toasty looking signs up - black, brown and sort of tan… I said if you really want to do a good job, you take that hot dog lettering and you make it pink and orange, my daughters favorite colors for her birthday party ever since she was 3 years old.

Imogen Cunningham

The reason during the 1920s that I photographed plants was that I had three children under the age of 4 to take care of, so I was cooped up … I had a garden available and I photographed them indoors. Later when I was free I did other things.

A letter from Tealia Ellis Ritter (co-curator of Designing Women III: MOTHER)

I’m in the darkroom and there’s a picture in my mind, as well as on the easel in front of me. The negative in my enlarger depicts my two children; the image I see in my mind’s eye is of the artist Ruth Asawa, seated on the ground amongst her hanging wire sculptures. Woven through the frame of the photo, and twisted around the hanging wire works, are her four children. Asawa appears in the back of the frame, wearing a hat, her head facing down... working. The children that surround her crouch and sit, unspooling the wire. In the foreground a naked baby, all rolls and flesh, sits sucking on a bottle. The square black and white image created by Imogen Cunningham, a mother of three, in 1957 titled “Ruth Asawa and her children,” has come to occupy a special corner of my mind. The corner that has weeded out thousands of images, viewed over a number of years as a photographer, logging only the few that have had lasting meaning. The image occupies this place because it simply and beautifully relays a truth I know. The truth of an artist and mother, children and art living together, influencing one another, interrupting one another, children as assistant, children as source of strength and source of exhaustion. It exemplifies the focus and determination necessary to create art and life.

I am in my mind with this image when I read an article in the New York Times in July of 2018 titled “ Curator Says MoMA PS1 Wanted Her, Until She Had a Baby.” In the article, Nikki Columbus, a Harvard graduate, curator and former editor of Artforum and Parkett, describes her experience with MoMA PS1 during the process of being hired as a curator at the museum. A process that was, according to Columbus, abruptly ended once she delivered her son. In 2019 MoMA PS1 settled the claim Columbus filed under the NYC Gender, Pregnancy and Caregiver Discrimination Act for an undisclosed amount, agreeing to rewrite their written policies designed to protect women as part of the settlement.

The image and the article compel me to research maternity discrimination and lead me to a Harvard study and the concept of the “Motherhood Penalty,” which describes the unconscious bias that institutions and society at large hold that women with children are less committed to their jobs, leading to lower wages, less opportunity for promotion and firings due to pregnancy. Men with children, however, are largely conceptualized as more responsible and committed to their employment because they are viewed as breadwinners. My research does not shock me. I don’t think it shocks many women. What does shock me is the visual disconnect between the messages seen on television, in print and on social media, celebrating the family and “baby bumps”, paired with the reality that the US is the only industrialized nation with no federal paid family leave.

I conclude that I am ignorant and decide to seek out information on women in the arts, who were or are also mothers.

The result of this research is a flood of beauty and depth of thought, of perseverance and well earned admiration. The exhibition, Designing Women III: MOTHER, brings together the work of twenty eight historical and contemporary artists and designers, all mothers, who have made or are in the process of making contributions to the art and design landscape. The exhibition is by no means comprehensive; it is but a sliver of the brilliance that exists.

To stand amongst the historical pieces included in Designing Women III: MOTHER offers a compelling look at the work and careers of the historical artists and designers, such as Louise Bourgeois, Eva Zeisel and Imogen Cunningham, noting the struggles that appeared along their paths of motherhood/creator and their eventual critical success. Living legends like Faith Ringgold, Maria Pergay and Loretta Pettway Bennett all of whom produced works, both political and formal, bridging the Civil Rights Movement and the Women’s Liberation Movement, serve as present day luminaries. To look at the works of many of the contemporary artists and designers exhibited, is to view the output of those that are in the struggle presently, navigating the roles of mother and artist/designer during a global pandemic. Their paths are still unfolding. They are the lives in process, the bodies of work still undetermined. Each a link in the chain of trailblazers.

WORKS BY

Carmen Winant

Carolyn Salas

Charlotte Perriand

Elizabeth Atterbury

Eva Zeisel

Faith Ringgold

Gae Aulenti

Golnar Adili

Hannah Whitaker

Hillary Petrie / Egg Collective

Imogen Cunningham

Jean Pelle / PELLE

Kai Avent-deLeon

Katrina Vonnegut / Vonnegut Kraft

Kelly Behun

Lella Vignelli / Vignelli Associates

Line Vautrin

Loretta Pettway Bennett / Gees Bend

Louise Bourgeois

Lucia DeRespinis

Luna Paiva

Maria Pergay

Natasha & Helena Sultan / Konekt

Rachel Cope / Calico Wallpaper

Renate Müller

Shawna X

Tahereh Fallahzadeh

Tealia Ellis Ritter

SPECIAL THANKS TO

Bruce Silverstein

Demisch Danant

Greg Kucera Gallery

Harlan & Weaver

J. Lohmann Gallery

Magen H Gallery

Maison Gerard

Marinaro Gallery

Mrs. Gallery

R & Company

Susanna Gold Gallery

The Imogen Cunningham Trust

The Easton Foundation

Sacred Pact